John Corlis: 19th Century Businessman

By Michael R. Veach

Special Collections Assistant

About |

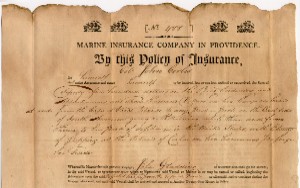

John Corlis (1767-1839) started

life as a merchant in Providence,

R.I. He was involved in the shipping

industry and was a partner in a gin

distillery in Providence. He serves as a

good example of an individual of the

growing upper-middle class in New

England. He made sure his children

received good educations.

His son Charles became a

midshipman on the frigate

USS Congress. Corlis was

involved in the overseas

trade and invested in several

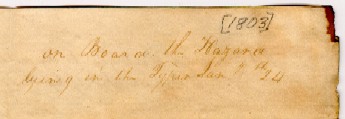

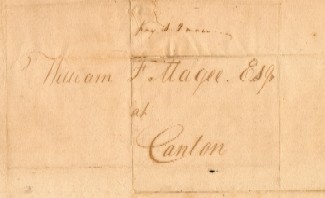

merchant ships. This

collection includes letters

written from the captain

of the merchant ship Hazard

while trading furs in

Canton, China, in 1803.

Corlis’s first setback as a

businessman occurred when

the Spanish government

seized the Hazard off the

coast of Chile in 1799. The Spanish

government seized another ship, the

Mary Ann, in 1805 near modern day

Uruguay. The loss of this cargo resulted

in Corlis and his partners fighting a

20-year legal battle to recover their investment. These suits were made even

more complicated by regime changes

during the Napoleonic Era and by

revolution in South America. Corlis

and his partners placed great hope in

the 1819 Adams-Onis Treaty by which

the United States acquired Florida and

claims by U. S. citizens against Spain

were to be settled. Unfortunately for

Corlis and his fellow investors, they

ultimately received only a small percentage

of their claim.

John Corlis (1767-1839) started

life as a merchant in Providence,

R.I. He was involved in the shipping

industry and was a partner in a gin

distillery in Providence. He serves as a

good example of an individual of the

growing upper-middle class in New

England. He made sure his children

received good educations.

His son Charles became a

midshipman on the frigate

USS Congress. Corlis was

involved in the overseas

trade and invested in several

merchant ships. This

collection includes letters

written from the captain

of the merchant ship Hazard

while trading furs in

Canton, China, in 1803.

Corlis’s first setback as a

businessman occurred when

the Spanish government

seized the Hazard off the

coast of Chile in 1799. The Spanish

government seized another ship, the

Mary Ann, in 1805 near modern day

Uruguay. The loss of this cargo resulted

in Corlis and his partners fighting a

20-year legal battle to recover their investment. These suits were made even

more complicated by regime changes

during the Napoleonic Era and by

revolution in South America. Corlis

and his partners placed great hope in

the 1819 Adams-Onis Treaty by which

the United States acquired Florida and

claims by U. S. citizens against Spain

were to be settled. Unfortunately for

Corlis and his fellow investors, they

ultimately received only a small percentage

of their claim.

Corlis also made investments in the Yazoo Land Company. This company did not hold proper title to the lands they were selling, and once again Corlis was involved in legal disputes that lasted for over 20 years. Other factors also added to the hardships he faced living in New England. The War of 1812 hurt his shipping interest when the coastal embargo shut down the shipping industry for several years. This embargo also hurt his distilling business because he could not receive enough grain to supply his distillery. On Jan. 4, 1814, he wrote, “Who in this nation could have anticipated an embargo on the coast trade, it does indeed look to me more a hostility to New England than Old England.”

In 1815 Corlis decided that his best course of action was to move to Kentucky. He bought a farm in Bourbon County and moved his family west and south but continued to return to Providence often in order to address his legal problems. He also used his New England business ties to fund several mercantile ventures in Kentucky, including a distillery.

Life in Kentucky was different than

life in Providence. Corlis found that

he had to hire slaves to help run the

farm. He and his wife, Susan, were

very uncomfortable with the institution

of slavery, and many of their letters

reflect this fact. Susan explained this

feeling in a letter dated May 6, 1821.

She described how beautiful and green

the farm was in the spring of that year;a beauty she felt was marred only by

the fact that Kentucky was a slave state.

There are a series of letters in the collection

that recount how one of their hired

slaves, Ezekiel, ran away after getting

into a fight with a white man. Corlis

lamented that they could not better

protect Ezekiel from this “scoundrel of

a man,” thus causing him to run away.

Life in Kentucky was different than

life in Providence. Corlis found that

he had to hire slaves to help run the

farm. He and his wife, Susan, were

very uncomfortable with the institution

of slavery, and many of their letters

reflect this fact. Susan explained this

feeling in a letter dated May 6, 1821.

She described how beautiful and green

the farm was in the spring of that year;a beauty she felt was marred only by

the fact that Kentucky was a slave state.

There are a series of letters in the collection

that recount how one of their hired

slaves, Ezekiel, ran away after getting

into a fight with a white man. Corlis

lamented that they could not better

protect Ezekiel from this “scoundrel of

a man,” thus causing him to run away.

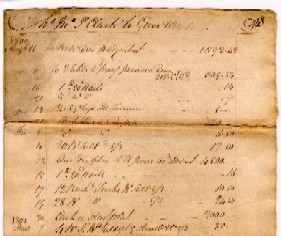

While in Kentucky, Corlis became

a tobacco merchant. He bought local

tobacco in Kentucky and shipped it

down river on flatboats, and later by

steamboat, to New Orleans for shipment

to European markets. He made

many of these trips himself, and his

letters home often describe the country

through which he passed and the

people with whom he was traveling.

After arriving in New Orleans, he took

passage on a ship sailing to Providence

in order to settle business affairs.

Sometimes he hired men to deliver the

tobacco to New Orleans, as he needed

to make the direct overland trip from

Kentucky to New England. As a businessman

he often had

his employees report the

prices of other commodities

in New Orleans to

him, which he considered

as possible investments.

Always looking for an

investment in the future,

Corlis had his son look

into the possibility of

starting a vineyard on

the farm.

While in Kentucky, Corlis became

a tobacco merchant. He bought local

tobacco in Kentucky and shipped it

down river on flatboats, and later by

steamboat, to New Orleans for shipment

to European markets. He made

many of these trips himself, and his

letters home often describe the country

through which he passed and the

people with whom he was traveling.

After arriving in New Orleans, he took

passage on a ship sailing to Providence

in order to settle business affairs.

Sometimes he hired men to deliver the

tobacco to New Orleans, as he needed

to make the direct overland trip from

Kentucky to New England. As a businessman

he often had

his employees report the

prices of other commodities

in New Orleans to

him, which he considered

as possible investments.

Always looking for an

investment in the future,

Corlis had his son look

into the possibility of

starting a vineyard on

the farm.

Investments and improvements required money. Money was a major concern to Kentuckians of Corlis’s era. There was a shortage of specie, and the state debated issuing paper money. Corlis was against this short-term solution. He had experienced a bad paper money solution in Rhode Island in 1786 and believed the results would be similar in Kentucky. He later used his connections in the east to purchase tobacco with New England bank notes rather than the “western currency.”

John Corlis struggled in business

until his death in 1839. His losses in

the Yazoo land scandal and to the

Spanish government kept him working

until the end of his life. His desire to

maintain family ties with family that

had remained in New England and

business associates  there resulted in

letters from him in Kentucky, and his

frequent travels east resulted in letters

back to Kentucky. He kept these letters

as a family record and also to chronicle

his business enterprises.

there resulted in

letters from him in Kentucky, and his

frequent travels east resulted in letters

back to Kentucky. He kept these letters

as a family record and also to chronicle

his business enterprises.

John Corlis’s family ultimately did prosper in Kentucky. After his death they continued correspondence as they became scattered, and a wealth of information can be found in this collection. John Corlis’s children and grandchildren were well educated and were often teachers and ministers. Religion and education were often the subjects of their correspondence, as well as descriptions of the towns in which they lived and worked. The Corlis-Respess Family Papers are well used by researchers, and The Filson is pleased to have them as part of its collection.

The Filson Historical Society

1310 South Third Street - Louisville, KY

40208

Phone: (502) 635-5083 Fax: (502) 635-5086

Hours

The Ferguson Mansion and Office

Monday - Friday: 9 am. - 5 pm.

Saturday and Sunday closed

Library

Monday - Friday: 9 am. - 5 pm.

Saturday: 9 am. - 12 noon