Political Corruption...19th Century Style

By Judith Partington

Head Librarian

About |

When George Washington took office as the first president of

the United States in 1789, there were no formal party organizations. He

and his compatriots shared a common eighteenth century aversion to political

parties, believing them to be too divisive for the stability of a new nation.

When George Washington took office as the first president of

the United States in 1789, there were no formal party organizations. He

and his compatriots shared a common eighteenth century aversion to political

parties, believing them to be too divisive for the stability of a new nation.

Over time, however, differences of opinion over the interpretation of the Constitution, the nature of business and of foreign and economic policies and the development of highly sectional interests necessitated the formation of a two-party system. Initially, rather than being divisive in nature, the two-party system tended to focus men’s views and bring them directly into one of two camps… the Federalists or the Democratic-Republicans.

Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury, championed the Federalist Party. Fearing that the new republic was too frail to compete with the great European powers, Hamilton envisioned a strong central bank supported by men of wealth and power… men who would not hesitate to invest in the nation’s future. He also envisioned America as a great industrial nation whose manufacturing output would raise the overall standard of living and create a middle class that would not be solely dependent upon agriculture. Unfortunately, all the measures put forth by Hamilton called for a highly centralized government, which had little appeal for a society having just freed itself from a European monarch. Favoring a decentralized government that would exercise as little control as possible, these men fell into the camp of Thomas Jefferson, a Democratic-Republican, who envisioned a strong agrarian nation of small, independent farmers.

In 1792 there was no contest

for the presidency. Washington

received the unanimous vote of

the electors, Federalists and Republicans

alike. Appealing to the

shopkeepers, artisans, and farmers

of the North on the basis of their

sympathy with the French Revolution

and to the southern planters

with their agrarian bias, the Democratic-

Republicans waged an effect

campaign for the second highest

office in the land. They were defeated,

however, and John Adams,

a Federalist who represented the

banking, fisheries, shipbuilding

and commercial interests of the

North, became vice-president.

In 1792 there was no contest

for the presidency. Washington

received the unanimous vote of

the electors, Federalists and Republicans

alike. Appealing to the

shopkeepers, artisans, and farmers

of the North on the basis of their

sympathy with the French Revolution

and to the southern planters

with their agrarian bias, the Democratic-

Republicans waged an effect

campaign for the second highest

office in the land. They were defeated,

however, and John Adams,

a Federalist who represented the

banking, fisheries, shipbuilding

and commercial interests of the

North, became vice-president.

When Washington stepped down in 1796, Adams was chosen to fill the first office in the land. Jefferson, who had resigned as Secretary of State in 1793 to retire to his beloved home in Virginia, had said that his retirement from public life was final, but alarmed over the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798, he ran against Adams in 1800 and won the election.

For the next 24 years a Virginia Dynasty occupied the White House with Jefferson being followed by James Madison and then James Monroe. All three were two-term presidents. During this time span the country grew from a population of a little over five million to almost ten million in 1820. Five new states, four of them in the West, participated in James Monroe’s last election and at the time of his second inauguration in 1820, the states of Ohio and Kentucky surpassed Massachusetts in population. Monroe’s last term ushered the country through an “Era of Good Feeling,” a time of political harmony that would soon dissipate in the election of 1824.

The election of 1824 was a

complicated one. Although

Monroe had been virtually unopposed

four years earlier, four men

ran for the presidency in 1824.

The Republican caucus gave the

official nomination to William

Harris Crawford, Monroe’s Secretary

of the Treasury. In doing

so they failed to take into account

other factions in the party, which

looked to John Quincy Adams,

Andrew Jackson and Henry Clay

for leadership. State conventions

ignored the choice of the congressional

caucus and nominated men

whose popularity rested in their

own regions. Adams and Clay

received the votes of their own

sections of the country as well as

those of states favoring internal

improvements and a protective

tariff. They lost votes in areas of

the West badly hit by the

Panic of 1819 and in the

South were states’ rights and

the protection of slavery

interests were paramount.

The election of 1824 was a

complicated one. Although

Monroe had been virtually unopposed

four years earlier, four men

ran for the presidency in 1824.

The Republican caucus gave the

official nomination to William

Harris Crawford, Monroe’s Secretary

of the Treasury. In doing

so they failed to take into account

other factions in the party, which

looked to John Quincy Adams,

Andrew Jackson and Henry Clay

for leadership. State conventions

ignored the choice of the congressional

caucus and nominated men

whose popularity rested in their

own regions. Adams and Clay

received the votes of their own

sections of the country as well as

those of states favoring internal

improvements and a protective

tariff. They lost votes in areas of

the West badly hit by the

Panic of 1819 and in the

South were states’ rights and

the protection of slavery

interests were paramount.

Andrew Jackson, the Hero of New Orleans, was a westerner with agrarian sympathies. He won the popular vote, carrying the southern states of Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee and North and South Carolina as well as the northern states of New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Maryland. With four candidates in the field, however, no one was able to obtain a majority of the electoral votes. This threw the decision into the House of Representatives where Henry Clay was now in a position to hand his electoral votes over to any one of the candidates, thereby choosing the next president. Observing tartly that killing 2,500 englishman at New Orleans hardly qualified one for the highest office in the land, Clay delivered his support to Adams who then became president. The affair might have ended there had Clay not made one of the worst decisions of his career… accepting Adams’ offer to become his Secretary of State. Jackson, who had initially been magnanimous over the loss of the presidency, now became enraged. He, and others, accused Clay of making a corrupt bargain with Adams. According to Jackson, he had been approached by Clay and his supporters with the same offer, but had turned them down. Clay quickly came to his own defense writing pamphlets in which he refuted Jackson’s claims. He maintained that he had chosen Adams because they shared the same nationalistic views and that he had a host of supporters who would attest to this.

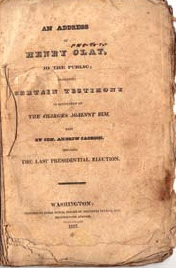

They did so, but to no avail.

The stigma of the “Bargain &

Sale” hung over Clay for the rest

of his career. Jackson referred to

him as the “Judas of the West.”

Clay refuted Jackson’s claims in

pamphlets addressed both to the

public and to his constituents.

The Filson Library has an 1825

edition of a pamphlet addressed

to “the people of the Congressional

district composed of the

counties of Fayette, Woodford,

and Clarke in Kentucky” which

was signed by Henry Clay. We

also have an address given at a

dinner in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania

in 1827. Our most recent purchase

is a pamphlet that is reputed to be

the only 1827 edition published in

Washington, D.C.

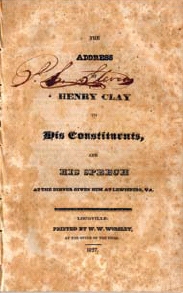

They did so, but to no avail.

The stigma of the “Bargain &

Sale” hung over Clay for the rest

of his career. Jackson referred to

him as the “Judas of the West.”

Clay refuted Jackson’s claims in

pamphlets addressed both to the

public and to his constituents.

The Filson Library has an 1825

edition of a pamphlet addressed

to “the people of the Congressional

district composed of the

counties of Fayette, Woodford,

and Clarke in Kentucky” which

was signed by Henry Clay. We

also have an address given at a

dinner in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania

in 1827. Our most recent purchase

is a pamphlet that is reputed to be

the only 1827 edition published in

Washington, D.C.

In spite of his claims that he was innocent of these charges, Clay never won a presidential election, although he ran for the office a total of five times. John Quincy Adams, like his father, held the office for only one term. Burning for revenge, Jackson and his followers ousted Adams in 1828 when the General ascended to the presidency to begin what became known as the Age of Jackson.

The Filson Historical Society

1310 South Third Street - Louisville, KY 40208

Phone: (502) 635-5083 Fax: (502) 635-5086

Hours

The Ferguson Mansion and Office

Monday - Friday: 9 am. - 5 pm.

Saturday and Sunday closed

Library

Monday - Friday: 9 am. - 5 pm.

Saturday: 9 am. - 12 noon