Henry H. Denhardt and Kentucky Politics in the 1920's

By Jacob F. Lee

Special Collections Assistant

About |

The recently cataloged papers of Lt. Gov. Henry H. Denhardt contribute to a better understanding of Kentucky politics in the 1920s. Born in Bowling Green in 1876, Denhardt earned a law degree from Cumberland University in Lebanon, TN and served as a prosecutor and later, a judge, in Warren County. Denhardt led a volunteer company in the Spanish-American War, and in 1916 he served with Gen. John J. Pershing in the expedition against Pancho Villa. During World War I, he fought on the Western Front, earning a commendation for valor. After the war, Denhardt returned to Kentucky and his law practice. In 1923, however, he turned away from his legal career to pursue his political ambitions. In a hard fought campaign, Denhardt defeated Republican candidate Ellerbe Carter to serve as Lieutenant Governor of Kentucky under Gov. William J. Fields. Four years later, Denhardt made a bid for the governorship, losing in a contentious Democratic primary.

The bulk of the Henry H. Denhardt

Papers collection focuses on these two elections,

including discussions of local organizing

and reports of reasons Kentuckians either

supported or opposed Denhardt. While his

correspondence reveals the inner workings

of political campaigns, it also exposes Kentuckians’

concerns over labor, race and other

issues.

The bulk of the Henry H. Denhardt

Papers collection focuses on these two elections,

including discussions of local organizing

and reports of reasons Kentuckians either

supported or opposed Denhardt. While his

correspondence reveals the inner workings

of political campaigns, it also exposes Kentuckians’

concerns over labor, race and other

issues.

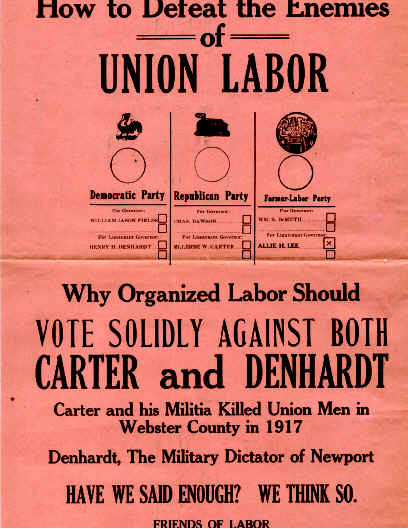

Organized labor is one of the most often discussed topics in Denhardt’s correspondence. In late 1921 and early 1922, Denhardt, as a colonel in the Kentucky National Guard, was in charge of troops sent to quell a riot stemming from a mill strike in Newport. The correspondence in the Denhardt Papers is, for the most part, 8 too biased to get an accurate view of what actually happened at Newport in 1921 and 1922. Denhardt adamantly defended his actions, while his opponents condemned his every move as dictatorial. Denhardt assured his constituents in the campaign that he had not been fighting the union but instead had been attempting to curb the efforts of violent infiltrators. In an August 1924 letter to P. H. Callahan, Denhardt wrote that his actions were “merely an effort to uphold the dignity and honor of the state against a few anarchists who were masquerading as friends of labor.” It is hard to know whether “anarchists” influenced the course of the strike, but certainly some of the strikers carried out extralegal violence. An anonymous 1922 letter from someone in Campbell County informed Denhardt of the actions of John Lutz, who “bragged about beating up scabs,” assaulting the Police Commissioner, hiring “negroes to beat up negro workmen” and attempting to “blow up the works.” The letter’s author also told Denhardt that Lutz had claimed to have murdered a soldier and “then helped tie the dead soldier’s arms and legs, fasten a weight to him, and throw him in the Licking River.” However, Denhardt’s troops probably reacted with unnecessary force. Numerous depositions in the collection report beatings of mill workers and other Newport residents at the hands of National Guardsmen. As with many military actions, it is unclear whether these attacks were authorized by Denhardt or if they were carried out by troops acting on their own accord.

Denhardt believed that his response to

the violence in Newport was understood by

most Kentuckians. In April 1923, Denhardt

stated that “practically every newspaper in

the State endorsed my actions in suppressing

the lawlessness in Newport,” and moreover,

he was given gifts by the citizens of Newport

and nearby Fort Thomas upon his departure,

indicating to him “that my actions there met

with the approval of the great majority of

the people.” However, his opponents saw

an opportunity. Throughout the 1923 election,

Republicans and labor advocates used

this incident as a basis to attack Denhardt.

Denhardt’s opponents labeled him a “Czar”

and “The Military Dictator of Newport.” In

July, the Kentucky State Federation of Labor

issued Bulletin No. 41, condemning, “This

doughty Colonel holds the record of being

first to use armor tanks in labor disputes,

and his record of terrorism and persecution

is without parallel or precedent in the history

of our nation.” The bulletin continued

to describe the scene in Newport, where

“the Mayor, County Judge, County Attorney,

Chief of Police and many others were arrested at the point of

bayonet.”

nearby Fort Thomas upon his departure,

indicating to him “that my actions there met

with the approval of the great majority of

the people.” However, his opponents saw

an opportunity. Throughout the 1923 election,

Republicans and labor advocates used

this incident as a basis to attack Denhardt.

Denhardt’s opponents labeled him a “Czar”

and “The Military Dictator of Newport.” In

July, the Kentucky State Federation of Labor

issued Bulletin No. 41, condemning, “This

doughty Colonel holds the record of being

first to use armor tanks in labor disputes,

and his record of terrorism and persecution

is without parallel or precedent in the history

of our nation.” The bulletin continued

to describe the scene in Newport, where

“the Mayor, County Judge, County Attorney,

Chief of Police and many others were arrested at the point of

bayonet.”

Denhardt spent much of the 1923 campaign defending his actions at Newport and establishing his record as a supporter of organized labor. In an August 1923 letter to J. S. Asbell, Denhardt wrote, “For weeks, every effort possible was made to avoid using force.” “I regret very much that my duty demanded the use of force,” Denhardt continued, “but any one who will stop to think must realize that under the circumstances, there was nothing for me to do but to obey orders and suppress the violence that was continuing in the city of Newport.” He also emphasized his support for unions, stating “I have always been and am now a staunch, loyal friend of organized union labor.” Denhardt and his supporters often brought up an incident in 1901, when he guarded miner James Woods, who was giving a pro-union speech in Earlington, KY. Although armed anti-union men had threatened Woods, Denhardt offered enough protection that Woods was able to give his speech. However, before they left town, they were “fired upon by some non-union miners who concealed themselves in the woods along the side of the road.” Denhardt’s supporters were also quick to criticize his opponent, Ellerbe Carter, who in 1917 had been in charge of troops who had put down a strike in Webster County. In October 1923, I. R. Jarvis, a former representative of the United Mine Workers of America, wrote a long letter to “The Voters of Kentucky” warning them of Carter’s actions. With reference to Carter, Jarvis stated, “I have met many military officers during my life but I do not believe I have ever seen any officer so autocratic, so deeply prejudiced against the ordinary working man.” “During the time he was in charge of State troops in Webster county,” Jarvis continued, “He was the most cruel and heartless military officer I have ever seen.” Jarvis concluded, “Coal miners, on strike for industrial freedom, were treated by him like dogs instead of human beings.” Denhardt’s strategy convinced many voters that he was not the anti-labor candidate the Carter campaign made him out to be. In October 1923, James M. Gilbert of Bell County wrote that he had been a Denhardt supporter since he had “learned of Mr. Carters actions in Webster Co. Miners Strike and also the Rail Strike at Corbin.”

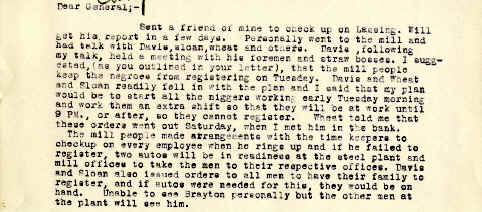

Race also played a role in Denhardt’s political campaigns. Denhardt

was not a race-baiter along the lines of Theodore Bilbo and some

of his other southern contemporaries, but he surely benefited from

efforts to curb black suffrage, as blacks regularly voted Republican

until the 1930s. A September 1923 letter from an unknown person

in Campbell County documents attempts to reduce the number of

black voters. In an effort to prevent blacks from registering to vote,

the mill owners would start all the blacks working early Tuesday

morning and work them an extra shift so that they would be at

work until 9 p.m., or after, so they could not register. As a candidate,

Denhardt also received warnings not to discuss the Ku Klux

Klan in his campaigns so as to not lose the political backing of the

then-powerful organization. In 1923, Ryland C. Musick of Breathitt

County told Denhardt, “Don’t mention Ku Klux.” When Denhardt

was preparing for his gubernatorial bid in April 1926, O. A. Barbee of

Davies County advised, “Keep in ‘the middle of the road’ on the Klan

question. I heard that at the last moment in your race for Lieutenant

Governor the Klan learned you were against that organization, and

issued instructions not to work for you.” The benefits of keeping

Klan support is evidenced by the November 1923 letter of Louis N.

Palmer, who wrote, “Newport is very sore, sorry that we did not have

more K.K.K. in the County, so that the showing would be better.”

Race also played a role in Denhardt’s political campaigns. Denhardt

was not a race-baiter along the lines of Theodore Bilbo and some

of his other southern contemporaries, but he surely benefited from

efforts to curb black suffrage, as blacks regularly voted Republican

until the 1930s. A September 1923 letter from an unknown person

in Campbell County documents attempts to reduce the number of

black voters. In an effort to prevent blacks from registering to vote,

the mill owners would start all the blacks working early Tuesday

morning and work them an extra shift so that they would be at

work until 9 p.m., or after, so they could not register. As a candidate,

Denhardt also received warnings not to discuss the Ku Klux

Klan in his campaigns so as to not lose the political backing of the

then-powerful organization. In 1923, Ryland C. Musick of Breathitt

County told Denhardt, “Don’t mention Ku Klux.” When Denhardt

was preparing for his gubernatorial bid in April 1926, O. A. Barbee of

Davies County advised, “Keep in ‘the middle of the road’ on the Klan

question. I heard that at the last moment in your race for Lieutenant

Governor the Klan learned you were against that organization, and

issued instructions not to work for you.” The benefits of keeping

Klan support is evidenced by the November 1923 letter of Louis N.

Palmer, who wrote, “Newport is very sore, sorry that we did not have

more K.K.K. in the County, so that the showing would be better.”

Denhardt seems to have mostly ignored racial issues during the

elections, neither publicly condemning nor promoting either side.

Sometimes, however, Denhardt could not overlook the racial discord10 The Filson summer 2007

of the 1920s. While Acting Governor in Gov.

William J. Fields’ absence, the June 1926

lynching of Primus Kirby forced Denhardt

to take action against T. H. Kelly, a constable

in Todd County, who allowed a mob to seize

Kirby while in custody. Kelly arrested Kirby

for murdering his wife and then shooting the

deputy sheriff who had first come to arrest

him. When Kelly returned the suspect to

Guthrie, a mob seized and lynched him.

Under Kentucky law, any law enforcement

officer who lost a prisoner received a suspension

from duty. Kelly was not exempt,

and he was removed from the constabulary.

In Kelly’s defense, some officials from Todd

County gave reports indicating that “possibly

Kelly could not have avoided giving him up.”

But Denhardt was not entirely convinced

stating that “there is little or no evidence

explaining the occurrences which took place

between the time of the arrest and the time

of the taking of the prisoner.” In an August

1826 letter to Denhardt, A. L. Hightower

presented information about the night of

the lynching that cast suspicion on Kelly’s

account of events. Hightower reported that

Kelly made two complete circles around the

town of Guthrie before taking the prisoner

to the jail and had carried two ropes in

his car on the night of the lynching. Most

incriminating was Hightower’s report that

Kelly had left “the Negro in Jail with the door

wide open for more than an hour with not an

officer on the ground, and a mob there howling,

“hang him.” Hightower offered to testify

against Kelly if necessary, despite threats on

his life. Hightower reported that several

prominent Todd Countians had threatened

to hang him on “the same tree where they

Hung the negro,” but he was most worried

about being murdered by Kelly or Marshal

D. T. Mimms, who would then claim self defense.

In 1929, Kelly applied to Denhardt

for reinstatement, but the only response in

the collection is Denhardt informing Kelly

that he would need to write to Gov. Fields.

Along with race, nationality was also a factor in Denhardt’s campaigns. During World War I, overzealous Americans persecuted German immigrants, who were thought to be un-American and disloyal. That anti-German sentiment continued to be a factor in politics in the 1920s. Denhardt’s German name prompted his opponents in the Bowling Green Council of the Junior Order United American Mechanics to state, “His name and his photograph are all that they imply, ‘A Hun, a Kaiser,’ who will rule or ruin.” However, Denhardt’s supporters used similar attacks when in October 1923, I. R. Jarvis complained of Ellerbe Carter’s role in quashing a 1917 strike in Webster County. Jarvis wrote, “His [Carter’s] demeanor on all occasions . . . was more like that of a German military officer than that of an American soldier.” It is unclear what effect the anti-German sentiment had on election results.

An interesting side note in the Denhardt Papers is the material on Denhardt’s role in the attempted rescue of Kentucky spelunker Floyd Collins. On Jan. 30, 1925, Collins began exploring Sand Cave near Cave City, only to be trapped while returning to the surface. Although Collins survived in the cave for at least two weeks, rescuers were unable to reach him until Feb. 16, by which time he was dead. As an officer in the National Guard, Denhardt was one of the commanders of the rescue efforts. Correspondence in the Denhardt Papers indicates the widespread emotional impact of Collins’ death. Clive Young from Denison, TX, discussed the emotional effect of the incident on his neighbors. F. E. Herrick of Cortland, NY, was so affected by Collins’ death that he wrote a poem about Collins, which he then sent to Denhardt. Also included in the collection are records of donations made to the Collins rescue fund by people across the United States.

The Henry H. Denhardt Papers provide an insider’s view into Kentucky politics in the 1920s. Because of Denhardt’s prominence as a political candidate and Lieutenant Governor, his correspondence is filled with references to the key issues in politics during his time.

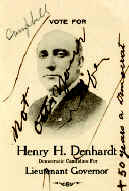

Unfortunately, the Denhardt Papers do not include much information on Denhardt’s life following his gubernatorial bid. In 1931, a political opponent shot Denhardt in the back on Election Day in Bowling Green. He survived and was appointed soon after to serve as Kentucky’s Adjutant General until 1935, at which point he retired. Denhardt’s retirement, however, was brief and violent. In November 1936, the body of Verna Taylor, Denhardt’s girlfriend, was found on the side of a country road in Shelby County, and Denhardt was accused of her murder. The trial ended in a hung jury, and in 1937, the night before a second trial was to begin, Taylor’s brothers gunned down Denhardt on the streets of Shelbyville. Although the Denhardt Papers do not include information on the last years of Denhardt’s life, the material in the collection covers his political career in depth, shining new light onto Kentucky politics in that era. MIDDLE p.8: Photograph of Henry H. Denhardt from a campaign pamphlet urging voters to elect Denhardt. Across Denhardt’s face, a Campbell County voter scrawled “Not on your life.” Henry H. Denhardt Papers. TOP p.9: Anonymous letter from September 1923 describing efforts to reduce black voter registration. Henry H. Denhardt Papers. ABOVE: A pro-labor campaign poster from Campbell County depicting the military force used in Newport in 1922. Henry H. Denhardt Papers. RIGHT: A campaign poster urging voters to support the Farmer-Labor Party candidate instead of Denhardt. Henry H. Denhardt Papers.

![]()

The Filson Historical Society

1310 South Third Street - Louisville, KY 40208

Phone: (502) 635-5083 Fax: (502) 635-5086

Hours

The Ferguson Mansion and Office

Monday - Friday: 9 am. - 5 pm.

Saturday and Sunday closed

Library

Monday - Friday: 9 am. - 5 pm.

Saturday: 9 am. - 12 noon