20th Century Distilling Papers at The Filson

By Michael R. Veach

Special Collections Assistant

About |

The distilling history for the 20th century can be divided into three phases – pre-prohibition (1901-1919), prohibition (1920-1933) and the post prohibition (1934-2000) era of modern whiskey production. The first two phases had a huge impact on defining the third phase. A researcher can find sources from all three phases of distilling history at The Filson.

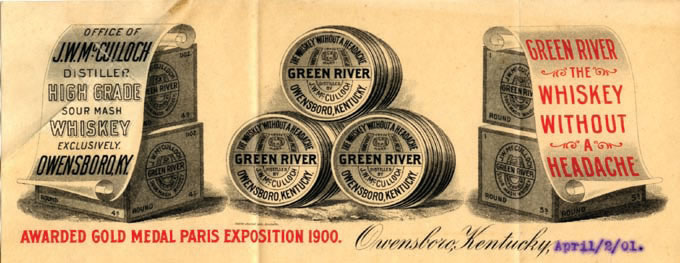

The first phase, pre-prohibition, was dominated by industry disputes and the growing prohibition movement. The Filson has three scrapbooks in the Taylor-Hay Family Papers with many newspaper and magazine articles from this period of turmoil. E. H. Taylor, Jr. and his Old Taylor Distillery produced straight whiskey and was involved in these political disputes. The Bottled-in-Bond Act of 1897 caused the first of these disputes. The act provided for whiskey to be produced under government supervision that was all the product of one distillery, made in the same season and aged for at least four years in bonded warehouses and bottled at 100 proof. The year 1901 was the first year that these requirements were all met and bonded whiskey was available on the market. The problem was that the public was not aware of the act and bonded whiskey was slow to catch on in the market place. The producers of straight whiskey took up the task of educating the public as to what bonded whiskey was and did so at the expense of the producers of blended whiskey or “rectifiers.” The straight whiskey producers tried to exclude the rectifiers from participating in the Kentucky exhibit at the St. Louis Exposition of 1903. They wanted the state of Kentucky to recognize “straight” whiskey, Bottled-in-Bond, as the only true “Kentucky Whiskey.” The rectifiers opposed and there are many clippings in the Taylor-Hay scrapbooks about the dispute.

The first phase, pre-prohibition, was dominated by industry disputes and the growing prohibition movement. The Filson has three scrapbooks in the Taylor-Hay Family Papers with many newspaper and magazine articles from this period of turmoil. E. H. Taylor, Jr. and his Old Taylor Distillery produced straight whiskey and was involved in these political disputes. The Bottled-in-Bond Act of 1897 caused the first of these disputes. The act provided for whiskey to be produced under government supervision that was all the product of one distillery, made in the same season and aged for at least four years in bonded warehouses and bottled at 100 proof. The year 1901 was the first year that these requirements were all met and bonded whiskey was available on the market. The problem was that the public was not aware of the act and bonded whiskey was slow to catch on in the market place. The producers of straight whiskey took up the task of educating the public as to what bonded whiskey was and did so at the expense of the producers of blended whiskey or “rectifiers.” The straight whiskey producers tried to exclude the rectifiers from participating in the Kentucky exhibit at the St. Louis Exposition of 1903. They wanted the state of Kentucky to recognize “straight” whiskey, Bottled-in-Bond, as the only true “Kentucky Whiskey.” The rectifiers opposed and there are many clippings in the Taylor-Hay scrapbooks about the dispute.

The Bottled-in-Bond Act is often considered one of the first laws leading to the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 because it set strict standards for the production of bonded whiskey. The struggle with the rectifiers over bonded whiskey became an all out war after the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act. The act called for defining food and drugs in order to regulate their production and the big question became “what is whiskey?” President Theodore Roosevelt and his Chief Chemist of the Food and Drug Administration, Harvey Wiley, favored a very tough interpretation of the  law saying that only “straight” whiskey with no additives other than water could be called whiskey and other products that added neutral spirits (alcohol distilled at higher than 180 proof), coloring and flavoring agents (such as caramelized sugar and prune juice) had to be called “imitation” whiskey. This led to a legal battle between the straight whiskey producers and the rectifiers. The three year long dispute was finally resolved when President Taft decided to act as moderator and hear both sides of the case and make a decision settling the matter. In December of 1909, Taft announced the results of his hearings with the “Taft Decision” that formally defined the types of whiskey still present today. Taft said that for a whiskey to be called “straight,” water was the only thing that could be added. If anything other than water was added to the whiskey, it had to be called a “Blended” whiskey.

law saying that only “straight” whiskey with no additives other than water could be called whiskey and other products that added neutral spirits (alcohol distilled at higher than 180 proof), coloring and flavoring agents (such as caramelized sugar and prune juice) had to be called “imitation” whiskey. This led to a legal battle between the straight whiskey producers and the rectifiers. The three year long dispute was finally resolved when President Taft decided to act as moderator and hear both sides of the case and make a decision settling the matter. In December of 1909, Taft announced the results of his hearings with the “Taft Decision” that formally defined the types of whiskey still present today. Taft said that for a whiskey to be called “straight,” water was the only thing that could be added. If anything other than water was added to the whiskey, it had to be called a “Blended” whiskey.

The Filson has several sources from this period for the researcher. Again, the Taylor-Hay Family Papers and the scrapbooks contain many articles and clippings from this dispute, including a printed copy of the Taft Decision. The Taft Decision was not without controversy and both sides had their complaints about the settlement. President Taft was under pressure from both sides of the issue and was grateful for any political support offered. In the papers of Kentucky Governor Augustus E. Willson, there is a letter from President Taft expressing his appreciation for Governor Willson’s support of his decision. The Filson’s Library also has many sources dealing with the “What is Whiskey” question.  There are rare trade magazines in the collection with articles on the subject such as “Mida’s Criteria,” published in Chicago, “Bonfort’s Wine and Spirit Bulletin,” published in New York City and “Barrels and Bottles,” a magazine published by the straight whiskey side in the Pure Food and Drug Act conflict over defining whiskey.

There are rare trade magazines in the collection with articles on the subject such as “Mida’s Criteria,” published in Chicago, “Bonfort’s Wine and Spirit Bulletin,” published in New York City and “Barrels and Bottles,” a magazine published by the straight whiskey side in the Pure Food and Drug Act conflict over defining whiskey.

Prohibition changed the nature of the distilling industry. The Filson Library has many books discussing the prohibition era of the 1920s and the prohibition movement. One book that is of particular interest is George Garvin Brown’s “The Holy Bible Repudiates “prohibition.” This is a book published by the founder of Brown-Forman in 1910 as an argument for true temperance and not prohibition, using the Bible to support his arguments. Both sides of the issue are represented in papers found in the special collections department, with pro-prohibition sentiments being found in collections such as the Young E. Allison Papers and the anti-prohibition arguments best found in the papers of Henry Watterson and the editorials he wrote. The Filson’ photographic collection is also a rich source of material. It has several photographs taken in Louisville at the time of repeal and a photograph album of the Brown-Forman Distillery just prior to the repeal of prohibition. The political image of prohibition can be found in some of the Van Leshout collection of political cartoons.

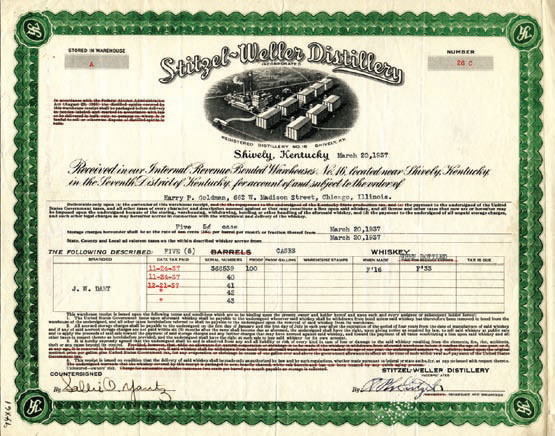

On Dec. 5, 1933, prohibition was repealed. The distilling industry was free to produce whiskey in Kentucky once again, but they had learned a valuable lesson with prohibition. Hoping to keep the government from making even tougher regulations, the industry created rules and regulations that were self-monitoring. These rules included the regulations from the Taft Decision defining whiskey, but went further, limiting the way whiskey could be packaged and sold. Barrels were no longer a legal package for the open market, replaced by bottles as the only legal package for distilled spirits sold to the public. The use of bottles meant that brand names and labels became a very important part of the industry. The Filson has a very good collection of whiskey labels from the period after repeal. Barrels of whiskey still were sold, just not to the public. Warehouse receipts from the distilleries were used to keep track of ownership of whiskey barrels. The United Distillers collection of receipts from the 1940s and 1950s has samples from several distilleries in Kentucky. New distilleries were built after prohibition

On Dec. 5, 1933, prohibition was repealed. The distilling industry was free to produce whiskey in Kentucky once again, but they had learned a valuable lesson with prohibition. Hoping to keep the government from making even tougher regulations, the industry created rules and regulations that were self-monitoring. These rules included the regulations from the Taft Decision defining whiskey, but went further, limiting the way whiskey could be packaged and sold. Barrels were no longer a legal package for the open market, replaced by bottles as the only legal package for distilled spirits sold to the public. The use of bottles meant that brand names and labels became a very important part of the industry. The Filson has a very good collection of whiskey labels from the period after repeal. Barrels of whiskey still were sold, just not to the public. Warehouse receipts from the distilleries were used to keep track of ownership of whiskey barrels. The United Distillers collection of receipts from the 1940s and 1950s has samples from several distilleries in Kentucky. New distilleries were built after prohibition

and the Taylor-Hay papers include material from the K. Taylor Distillery, opened after repeal as the Taylor family tried to get back into the distilling business. The Library also has issues of rare trade magazines from the 1930s. The May 1936 issue of the trade magazine “Spirits” contains a section detailing Kentucky’s distilling families and provides information on those who worked in the newly opened distilleries.

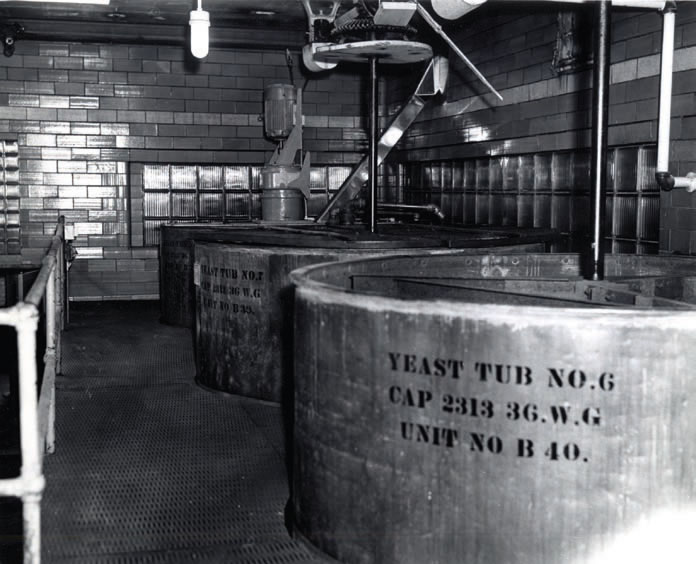

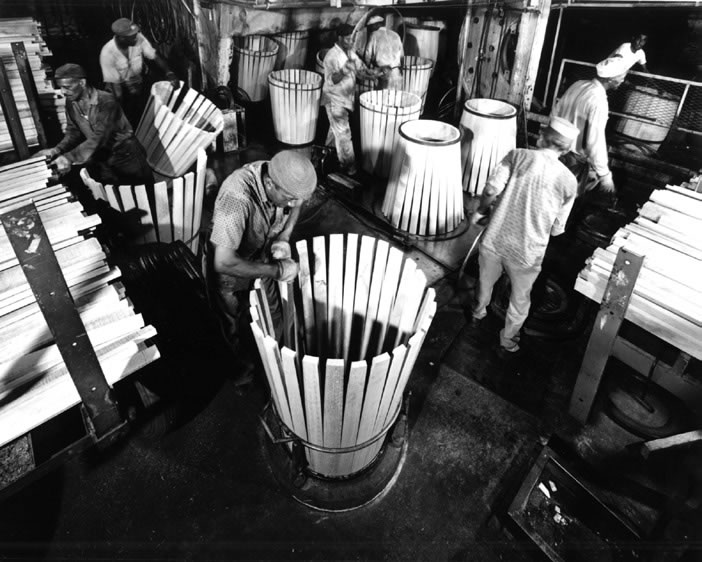

The period after the second World War was a period of growth for the distilling industry. The United Distillers photograph collection has many photographic examples of distillery construction projects as distilleries expanded production to meet demand for their products. This same collection also contains images of employees in Kentucky distilleries and marketing projects like the small barrel of I.W. Harper given to Winston Churchill during a visit to the United States.

The period after the second World War was a period of growth for the distilling industry. The United Distillers photograph collection has many photographic examples of distillery construction projects as distilleries expanded production to meet demand for their products. This same collection also contains images of employees in Kentucky distilleries and marketing projects like the small barrel of I.W. Harper given to Winston Churchill during a visit to the United States.

A very significant collection of 20th century distilling papers are the Edwin Foote Papers. Foote is a retired Master Distiller from both the Seagram Americas and United Distillers Productions. His papers include many items of interest, but the most detailed papers are his logbooks kept as a distiller at the Old Fitzgerald Distillery in Shively. The logbooks start when Foote was hired by Old Fitzgerald after retiring from Seagram in 1984 and continue until the distillery was closed in 1992. These logs show the change in recipe of the whiskey that was made as the distillery cut production costs and increased output. There are also examples of workers’ union contracts from both Seagram and Old Fitzgerald. Foote also collected photographs of all of the Master Distillers who worked at the Stitzel-Weller Distillery, later renamed the Old Fitzgerald Distillery, before him.

Pre-prohibition, prohibition and the modern post-prohibition phases of the 20th century whiskey industry will be subjects of research as more people write about distilling history. Kentucky Bourbon production is growing as the product finds its way into international markets and as the consumers of bourbon become interested in its rich history.

The Filson has many good sources of distilling history in its collections. These papers go back to the early days of Kentucky’s history up to the end of the 20th century. Anyone interested in researching the history of Kentucky Bourbon and the distilling industry producing bourbon whiskey should make The Filson Historical Society a required place to visit and plan on spending more than a day doing research.

The Filson Historical Society

1310 South Third Street - Louisville, KY 40208

Phone: (502) 635-5083 Fax: (502) 635-5086

Hours

The Ferguson Mansion and Office

Monday - Friday: 9 am. - 5 pm.

Saturday and Sunday closed

Library and Special Collections

Monday - Friday: 9 am. - 5 pm.

First Saturday of each month: 9 am. - 4 pm