Defining Events: Louisville's Natural Disasters

By Mark V. Wetherington, PhD

Director

About |

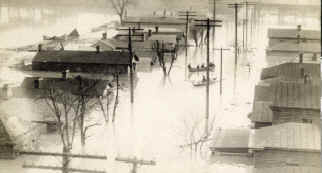

This January marked the 70th anniversary of the Flood of 1937, a

natural disaster that inundated the Ohio River Valley from one end to the other.

It was one of those calamities that marked the collective memory of the people who experienced it.

the people who experienced it.

Almost every Louisville generation could point to such a defining event—earthquake, flood or tornado. Its people could recall where they were when disaster struck, and what happened to them, their loved ones and their community.

Today, images of contemporary disasters are brought to us almost instantly and visually, even as they unfold, courtesy of technology. But before the widespread use of printed images, photographs, film and television, words primarily recorded disasters.

When tremors from the New Madrid earthquake reached Louisville

on December 16, 1811 one citizen wrote: "It seems as if the surface

of the earth was a boat and set in motion by a slight application of immense

power...all order is destroyed." Others "believed that mother Earth,

as she heaved and struggled,  was

in her last agony." Buildings began to "oscillate largely and

irregularly, and grind against each other...chimneys, parapets and gable ends

break...and topple to the ground."

was

in her last agony." Buildings began to "oscillate largely and

irregularly, and grind against each other...chimneys, parapets and gable ends

break...and topple to the ground."

Twenty years later, the Flood of 1832 covered the city’s low-lying areas. This "unparalleled .ood" destroyed much of the first generation of Louisville’s waterfront architecture. One historian wrote: "Nearly all the frame buildings near the river were either floated off or turned over and destroyed." Business came to a standstill.

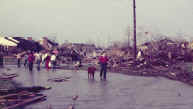

The 1890 Louisville Cyclone was among the early disasters

documented extensively by images and words. (See The Filson, Spring 2005). On March 27th, the tornado cut across the

west end of town and destroyed homes, businesses, warehouses and churches. It

killed nearly 100 people, approximately the same number of Louisvillians who

lost their lives by the Flood of 1937. Within recent memory, the Tornado of 1974

stands out as the most destructive.

words. (See The Filson, Spring 2005). On March 27th, the tornado cut across the

west end of town and destroyed homes, businesses, warehouses and churches. It

killed nearly 100 people, approximately the same number of Louisvillians who

lost their lives by the Flood of 1937. Within recent memory, the Tornado of 1974

stands out as the most destructive.

We know about the Flood of 1937 and the Tornado of 1974 because they both exist in the memories of those who lived through them, and were richly documented by images and words. To a lesser extent we can say the same about the Flood of 1913, documented in photographs by Filson president R. C. B. Thruston. We know less about the 1890 Louisville Cyclone because it is beyond our living memory and the documentary record is not as complete. And we know even less about the other 19th century natural disasters, and those that came before them.

As

important as the disasters themselves, are the meanings their survivors gave to

them as they dealt with the messy consequences —flooded and destroyed homes

and businesses, severely injured survivors, grieving citizens and funerals.

Louisvillians often reacted to these calamities by looking for a silver

lining. Survivors of the New Madrid earthquake believed the disaster was a

providential warning to improve "the morals of the town." Louisville

soon built its first church. For all the damage it did, the Flood of 1832 swept

away the cracked and weakened buildings that survived the earthquake and in the

end, had "but a temporary effect on the progress of the city."

As

important as the disasters themselves, are the meanings their survivors gave to

them as they dealt with the messy consequences —flooded and destroyed homes

and businesses, severely injured survivors, grieving citizens and funerals.

Louisvillians often reacted to these calamities by looking for a silver

lining. Survivors of the New Madrid earthquake believed the disaster was a

providential warning to improve "the morals of the town." Louisville

soon built its first church. For all the damage it did, the Flood of 1832 swept

away the cracked and weakened buildings that survived the earthquake and in the

end, had "but a temporary effect on the progress of the city."

The Flood of 1937 united the community in an effort to rescue survivors and rebuild the community. But the good, along with other factors, changed Louisville’s residential patterns and helped create a more segregated city. Did other disasters do the same? Did they carry with them consequences we have forgotten?

The

Courier-Journal has created a website to collect information on the Flood of

1937 (www.courier-journal.com/37flood). Written materials (letters, scrapbooks,

etc.) will be donated to The Filson after this project ends.

The

Courier-Journal has created a website to collect information on the Flood of

1937 (www.courier-journal.com/37flood). Written materials (letters, scrapbooks,

etc.) will be donated to The Filson after this project ends.

Let’s use the commemoration of the Flood of 1937 as an opportunity to better document other disasters in the city’s past. Half of the disaster dates I’ve mentioned took place in the 20th century; materials still exist to document these and even earlier disasters in our community and region. Please think of your own family’s disaster experiences and of the materials they preserved—photographs, diaries, letters, scrapbooks and printed materials—and consider donating them to The Filson so that their long reaching consequences can be studied and better understood today and in the future.

![]()

The Filson Historical Society

1310 South Third Street - Louisville, KY 40208

Phone: (502) 635-5083 Fax: (502) 635-5086

Hours

The Ferguson Mansion and Office

Monday - Friday: 9 am. - 5 pm.

Saturday and Sunday closed

Library

Monday - Friday: 9 am. - 5 pm.

Saturday: 9 am. - 12 noon