George S. Leland and Civil War Logistics

By Matthew E. Stanley

Filson Intern

About |

The word “logistics” derives from the Greek adjective logistikos,

meaning “skilled in calculating.” In that sense, its definition is appropriate

in describing how the Union Army utilized its logistical systems

to prevail in the American Civil War. In short, military logistics is

the discipline of maintaining large military forces in the field. This

practice often encompasses the acquisition of stores and their distribution,

as well as the maneuvering and coordinating of large armies

along bases of supply. When executed properly, as exemplified by

federal forces under Quartermaster Gen. Montgomery C. Meigs,

military logistics can be a deciding factor in an operation, campaign

or war.

The word “logistics” derives from the Greek adjective logistikos,

meaning “skilled in calculating.” In that sense, its definition is appropriate

in describing how the Union Army utilized its logistical systems

to prevail in the American Civil War. In short, military logistics is

the discipline of maintaining large military forces in the field. This

practice often encompasses the acquisition of stores and their distribution,

as well as the maneuvering and coordinating of large armies

along bases of supply. When executed properly, as exemplified by

federal forces under Quartermaster Gen. Montgomery C. Meigs,

military logistics can be a deciding factor in an operation, campaign

or war.

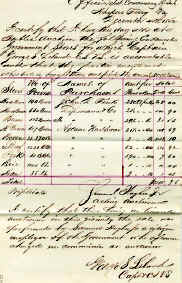

Capt. George S. Leland of the Office of Commissary Subsistence

in the Department of West Virginia, headquartered at Harper’s Ferry,

VA., and operating along the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad supply

artery, was but a “link in the chain” of broad Union logistical systems.

Nevertheless, his papers provide a detailed insight into the daily activities

of a Civil War quartermaster and the typical supply situation

of a Union field army. The Filson’s Leland collection, which spans

from 1862 to 1864, comprises of store estimates, invoices, lists of

provisions, and complaints from soldiers and local civilians. Leland

composed public letters, food orders, tallied railroad cargo, and

telegrams requesting rations and supplies. His offices also stocked

hospitals, transferred goods and evaluated troop numbers. From

Leland’s Papers, researchers can likewise determine the daily eating

habits of the men within his department. The evidence suggests that Union soldiers in

West Virginia consumed

salt bacon,

hard bread and Rio

coffee with expected

regularity. They also

used amenities such as soap, whisky and adamantine candles on a

daily basis.

invoices, lists of

provisions, and complaints from soldiers and local civilians. Leland

composed public letters, food orders, tallied railroad cargo, and

telegrams requesting rations and supplies. His offices also stocked

hospitals, transferred goods and evaluated troop numbers. From

Leland’s Papers, researchers can likewise determine the daily eating

habits of the men within his department. The evidence suggests that Union soldiers in

West Virginia consumed

salt bacon,

hard bread and Rio

coffee with expected

regularity. They also

used amenities such as soap, whisky and adamantine candles on a

daily basis.

Leland’s duties were wide-ranging. The captain acquired stores and equipage, upheld an inventory of detailed ration lists, addressed captured property and calculated how much subsistence a body of troops consumed over a period of time. Payment issued for services rendered by federal employees, including bricklayers, slaughterhouse workers and government bakers, was disbursed through Leland’s offices. Leland also received formal complaints regarding substandard rations. “There has been much complaint from Wheaton’s Brigade,” one officer informed. “The quality of the bread issued to them is inferior and badly baked. Put an end to this grumbling,” he warned. Another officer protested, “One Third of the hard bread issued to my command is unsound and totally unfit to be eaten.” Conversely, in Nov. 1863 under Special Orders No. 18, the department ordered Leland to “take charge of the [captured] Hershman, an alleged blockade runner.” In an unrelated duty, Leland was instructed to discharge deserter employees who had absconded from the government bake house in Annapolis, MD. From blockade runners to runaway cooks, Leland’s Papers underscore the variety of his responsibilities in the field.

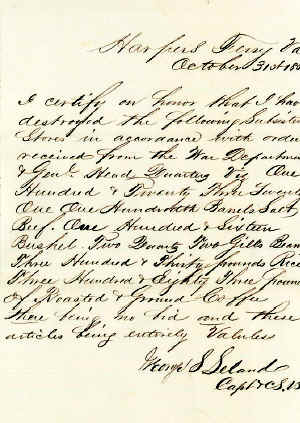

Leland also received food requests from impoverished civilians.

“Unless you offer me something, me and my children will suffer

. . . I see no possible way of getting along without your help,”

implored one distressed citizen. In other cases, Leland’s offices

provided compensation to civilians for military destruction. Under

Special Orders No. 133 in July 1864, Leland was “authorized

to issue rations [to families] in destitute conditions . . . or whose homes have been destroyed for military

purposes.” In some of the more fascinating

correspondence, Leland was responsible for

determining the fate of spoiled goods. His

offices pawned off “unsound stores” such as

“maggoty bacon, honey-combed by vermin,”

“musty beans” and “decayed salt beef ” to unsuspecting

local buyers. Though the practice

of peddling “goods unfit for use” was not

exclusive to his department, it is surprising

that Leland kept a catalog of such ominous

transactions. “I have sold at public auction

the following condemned government

stores,” he notified his superiors. Whatever

the outcome of such matters, the number

of sales to and requests from citizens speaks

to the multiplicity of Leland’s tasks as quartermaster.

my children will suffer

. . . I see no possible way of getting along without your help,”

implored one distressed citizen. In other cases, Leland’s offices

provided compensation to civilians for military destruction. Under

Special Orders No. 133 in July 1864, Leland was “authorized

to issue rations [to families] in destitute conditions . . . or whose homes have been destroyed for military

purposes.” In some of the more fascinating

correspondence, Leland was responsible for

determining the fate of spoiled goods. His

offices pawned off “unsound stores” such as

“maggoty bacon, honey-combed by vermin,”

“musty beans” and “decayed salt beef ” to unsuspecting

local buyers. Though the practice

of peddling “goods unfit for use” was not

exclusive to his department, it is surprising

that Leland kept a catalog of such ominous

transactions. “I have sold at public auction

the following condemned government

stores,” he notified his superiors. Whatever

the outcome of such matters, the number

of sales to and requests from citizens speaks

to the multiplicity of Leland’s tasks as quartermaster.

Historians are just beginning to appreciate the need for an understanding of the role of logistical preparations in modern military organization. The Filson’s George S. Leland Papers, which also includes a chart for converting the bulk amount of various types of subsistence into the corresponding number of troops, is sure to profit researchers working on Civil War army and supply studies. Although recent scholarship has contributed greatly to our understanding of how Civil War armies were maintained on the campaign trail, the need for studies of logistics remains.

![]()

The Filson Historical Society

1310 South Third Street - Louisville, KY 40208

Phone: (502) 635-5083 Fax: (502) 635-5086

Hours

The Ferguson Mansion and Office

Monday - Friday: 9 am. - 5 pm.

Saturday and Sunday closed

Library

Monday - Friday: 9 am. - 5 pm.

Saturday: 9 am. - 12 noon