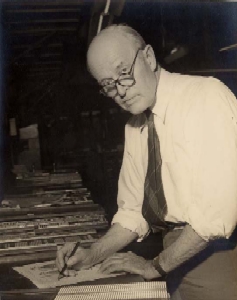

Tom Wallace, 1874-1961

The Tom Wallace Papers contains 23 cubic feet of Wallace’s correspondence, speeches and other material, documenting the prodigious career of this native Kentuckian who served as a journalist, a conservationist, and a promoter of friendship between the Americas.

By Noah Huffman

Special Collections Assistant

About |

With 23 cubic feet of Wallace’s correspondence, speeches and other material, the collection documents

the prodigious career of this native Kentuckian whose intellect, vigilance and tenacity garnered him

national recognition on three fronts – as a journalist, a conservationist and a promoter of friendship

between the Americas. Upon his death in 1961, The New York Times lauded Wallace as “a believer in the

editorial crusade” whose “vigorous pen” waged two major campaigns during his lifetime, “the fight for

conservation of the nation’s natural resources and a long campaign for the betterment of relations between

North and South America.” Fortunately, as part of the 20th Century Initiative, The Filson can now provide

scholars of journalism, conservation history and Latin American relations with access to this important collection

from the last century.

With 23 cubic feet of Wallace’s correspondence, speeches and other material, the collection documents

the prodigious career of this native Kentuckian whose intellect, vigilance and tenacity garnered him

national recognition on three fronts – as a journalist, a conservationist and a promoter of friendship

between the Americas. Upon his death in 1961, The New York Times lauded Wallace as “a believer in the

editorial crusade” whose “vigorous pen” waged two major campaigns during his lifetime, “the fight for

conservation of the nation’s natural resources and a long campaign for the betterment of relations between

North and South America.” Fortunately, as part of the 20th Century Initiative, The Filson can now provide

scholars of journalism, conservation history and Latin American relations with access to this important collection

from the last century.

Born in Hurricane, Crittenden County, Kentucky, in 1874, Tom Wallace received his early instruction

from a family tutor before attending Weaver’s Business College in Louisville and eventually Randolph Macon College

in Ashland, Virginia. Despite his academic promise, Wallace left school early and took a series of brief jobs as

a bookkeeper in Shelbyville, Ky.,  Richmond, Va., and New York City. It was during this period that he discovered

he “hated all kinds of business,” an attitude that became increasingly apparent with age. Swearing off the business

world, young Wallace and two adventurous friends set sail down the coast of Florida on a rickety catboat he

named the “Bluegrass.” As he recalled in an unpublished autobiography held at The Filson, the natural beauty of

the landscape and the abundance of wildlife he encountered left an indelible impression that later influenced his

career-long advocacy of scenic and wildlife preservation.

Richmond, Va., and New York City. It was during this period that he discovered

he “hated all kinds of business,” an attitude that became increasingly apparent with age. Swearing off the business

world, young Wallace and two adventurous friends set sail down the coast of Florida on a rickety catboat he

named the “Bluegrass.” As he recalled in an unpublished autobiography held at The Filson, the natural beauty of

the landscape and the abundance of wildlife he encountered left an indelible impression that later influenced his

career-long advocacy of scenic and wildlife preservation.

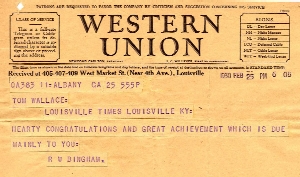

Returning home to Kentucky in 1900, the 26-year-old Wallace sought a new career path. He chose journalism and talked his way into an unpaid position as a police reporter at the Louisville Times, writing the column “Little Dramas of the Police Court.” Six weeks later the Louisville Dispatch offered Wallace a paid position, the first of several brief reporting jobs he held while honing his skills as a newspaperman. Eventually, Wallace landed back at the Louisville Times as its Washington correspondent. Impressed by his work for the Times, legendary editor Henry Watterson hired the relatively inexperienced Wallace as the youngest member of the Courier-Journal editorial staff in 1905. Over the next several years as an associate editor, Wallace studied under Watterson and, like his mentor, developed a reputation for boldness and brevity in his editorials. Echoing Watterson’s editorial philosophy, Wallace would later remark that “editorials should be no longer than a pencil,” and “an editorial page without spunk is bunk.”

In 1923, two years after the death of his revered chief, Wallace became

the head of the Louisville Times editorial page. He was named editor by owner/publisher Robert Worth Bingham

in 1930, where he remained until the Times’ age requirement forced him to retire in 1948. Although unhappy

about his early departure, Wallace continued to contribute to the Times as editor emeritus, in addition to authoring

numerous editorials and articles for national publications. During Wallace’s tenure and under owners R.W. and

Barry Bingham, the Times rose to national prominence. In recognition of Wallace’s leadership and integrity, he

received numerous professional honors, including serving as president of the American Society of Newspaper Editors from

1940 to 1941.

In 1923, two years after the death of his revered chief, Wallace became

the head of the Louisville Times editorial page. He was named editor by owner/publisher Robert Worth Bingham

in 1930, where he remained until the Times’ age requirement forced him to retire in 1948. Although unhappy

about his early departure, Wallace continued to contribute to the Times as editor emeritus, in addition to authoring

numerous editorials and articles for national publications. During Wallace’s tenure and under owners R.W. and

Barry Bingham, the Times rose to national prominence. In recognition of Wallace’s leadership and integrity, he

received numerous professional honors, including serving as president of the American Society of Newspaper Editors from

1940 to 1941.

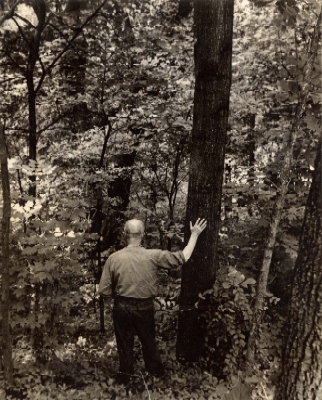

Although

recognized as one of the country’s most hard-hitting and respected editors, Wallace is best remembered for his

career-long fight to preserve the nation’s natural resources and scenic landscapes. At a time when newspapers and journalists immensely

influenced public opinion, Wallace used his fame as editor to both popularize and energize a nascent conservation

movement that had previously consisted of only a few elite “nature enthusiasts.”

Although

recognized as one of the country’s most hard-hitting and respected editors, Wallace is best remembered for his

career-long fight to preserve the nation’s natural resources and scenic landscapes. At a time when newspapers and journalists immensely

influenced public opinion, Wallace used his fame as editor to both popularize and energize a nascent conservation

movement that had previously consisted of only a few elite “nature enthusiasts.”

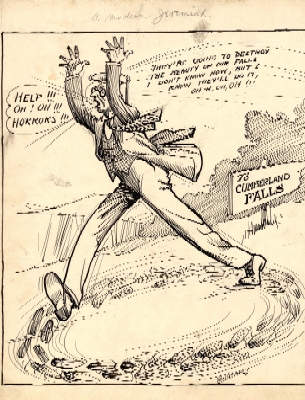

As a conservationist, Wallace’s

greatest triumph came in 1930 after he

spearheaded a five-year campaign to

prevent the construction of a hydroelectric

dam at Cumberland Falls.

Publishing over 200 editorials and

delivering countless speeches against

the Samuel Insull project, Wallace

unearthed a groundswell of public support

for saving the falls, thus persuading

native Kentuckian T. Coleman

duPont to purchase the Cumberland

Falls tract and donate it to the state

before the Federal Power Commission

could approve the dam. A legislative

fight quickly ensued, pitting Wallace

and his supporters against Governor

Flem Sampson and his pro-dam coalition.

Largely due to Wallace’s relentless

pressure, the Senate eventually voted

to approve the duPont Gift Acceptance

Bill over Sampson’s veto, effectively

saving the falls for future generations

of Kentuckians. Ultimately the victory

at Cumberland Falls won Wallace wide

acclaim in conservation circles and

effectively initiated him into the small

but emergent national movement.

generations

of Kentuckians. Ultimately the victory

at Cumberland Falls won Wallace wide

acclaim in conservation circles and

effectively initiated him into the small

but emergent national movement.

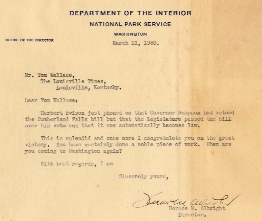

Through the “Cumberland Falls Fight” Wallace gained contacts with prominent conservationists nationwide from National Park Service Directors Stephen Mather and Horace Albright, to lay leaders like Gifford Pinchot and J.N. “Ding” Darling. These valuable contacts, coupled with his flair for argument and his unique position as editor of a respected newspaper, catapulted Wallace to the forefront of American conservation. In a 1957 letter, National Park Service Director Newton Drury dubbed him “the supreme philosopher in this business.”

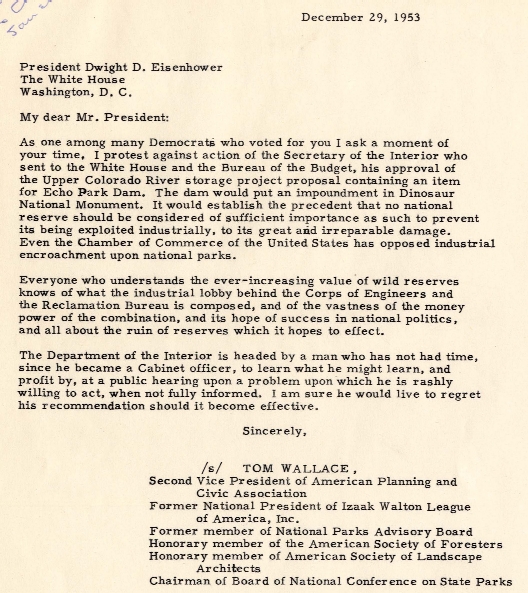

Because of his influence, a series of

organizations coveted Wallace’s leadership. In 1946 he was elected president

of the Izaak Walton League of

America, one of the earliest and most

influential conservation organizations.

In addition, he served as chairman

of the National Conference on State

Parks, Vice-President of the American

Planning and Civic

Association, and on

the Advisory Board

to the National Parks

Service. In these

various capacities,

Wallace lobbied

against high dams,

stream pollution and

strip mining, and

formulated policy for

the National Park  Service. Some 20

years after Cumberland

Falls, Wallace

led a campaign

against the proposed

Echo Park Dam in

Colorado during

the 1950s. After nearly a decade of

heated debate, Wallace and his fellow

preservationists convinced Secretary of

the Interior Douglas McKay to abandon

the project, one of the watershed

events in conservation history.

Service. Some 20

years after Cumberland

Falls, Wallace

led a campaign

against the proposed

Echo Park Dam in

Colorado during

the 1950s. After nearly a decade of

heated debate, Wallace and his fellow

preservationists convinced Secretary of

the Interior Douglas McKay to abandon

the project, one of the watershed

events in conservation history.

Throughout his life, Wallace argued that “preservation is our purpose,” abhorring “artificial improvements” of any kind – a stance that often brought him into conflict with more moderate conservationists. In recognition of his many achievements the University of Louisville established the Tom Wallace Chair of Conservation in 1956. The Tom Wallace Lake in Jefferson County Memorial Forest was also named in his honor.

In addition to his duties as editor

and amateur conservationist, Wallace

lent his talents to promoting better dialogue

between the Americas. He wrote

that for too long “we have indulged

a superiority complex with regard to

Latin Americans, who, as a result

have shrugged their shoulders.”

To combat this prevailing attitude,

Wallace and several other journalists

founded the Inter-American

Press Association (IAPA) in 1943 to

promote freedom of the press and

Pan-Americanism. Wallace served as

the group’s first president in 1945 and

was instrumental in its expansion until

his death in 1961. He presided over

conferences in Ecuador, Uruguay, Cuba

and Venezuela, often drawing the ire

of politicians like Juan Peron. Today

the IAPA boasts over 1,300 member

newspapers from Alaska to Chile and

remains committed to Wallace’s vision

of press freedom and hemispheric

solidarity.

In addition to his duties as editor

and amateur conservationist, Wallace

lent his talents to promoting better dialogue

between the Americas. He wrote

that for too long “we have indulged

a superiority complex with regard to

Latin Americans, who, as a result

have shrugged their shoulders.”

To combat this prevailing attitude,

Wallace and several other journalists

founded the Inter-American

Press Association (IAPA) in 1943 to

promote freedom of the press and

Pan-Americanism. Wallace served as

the group’s first president in 1945 and

was instrumental in its expansion until

his death in 1961. He presided over

conferences in Ecuador, Uruguay, Cuba

and Venezuela, often drawing the ire

of politicians like Juan Peron. Today

the IAPA boasts over 1,300 member

newspapers from Alaska to Chile and

remains committed to Wallace’s vision

of press freedom and hemispheric

solidarity.

Aside from their insights into 20thcentury

journalism, conservation and

Latin American relations, the Wallace

papers also provide valuable material

for scholars of Kentucky politics, the

New Deal era,

World War II and

race relations. In

a sense, Wallace’s

work as editor

put him at the

crossroads of nearly

every important

event and issue

during the first half

of the 20th century.

Aside from their insights into 20thcentury

journalism, conservation and

Latin American relations, the Wallace

papers also provide valuable material

for scholars of Kentucky politics, the

New Deal era,

World War II and

race relations. In

a sense, Wallace’s

work as editor

put him at the

crossroads of nearly

every important

event and issue

during the first half

of the 20th century.

In 1951, at the pinnacle of his long career, Wallace decided to donate his personal papers to The Filson, where he had been a longtime member. Although The Filson did not receive his papers until 2001, Wallace’s foresight and concern for preserving history have made this important 20th-century collection available to future researchers. When considering donating your personal papers, please keep The Filson in mind because, like Wallace, “preservation is our purpose.”

The Filson Historical Society

1310 South Third Street - Louisville, KY 40208

Phone: (502) 635-5083 Fax: (502) 635-5086

Hours

The Ferguson Mansion and Office

Monday - Friday: 9 am. - 5 pm.

Saturday and Sunday closed

Library

Monday - Friday: 9 am. - 5 pm.

Saturday: 9 am. - 12 noon