The Frances Ingram Papers, 1894-1953

By Jacob F. Lee

H.F. Boehl Summer Intern

About |

A recent addition to The Filson’s growing twentieth-century manuscript collection are the papers of

Louisville social worker Frances Ingram (1874-1954). Consisting of correspondence, pamphlets,

sociological reports, newspaper clippings, and lectures, Ingram’s papers thoroughly document Louisville’s

early-twentieth century reform movements.

A recent addition to The Filson’s growing twentieth-century manuscript collection are the papers of

Louisville social worker Frances Ingram (1874-1954). Consisting of correspondence, pamphlets,

sociological reports, newspaper clippings, and lectures, Ingram’s papers thoroughly document Louisville’s

early-twentieth century reform movements.

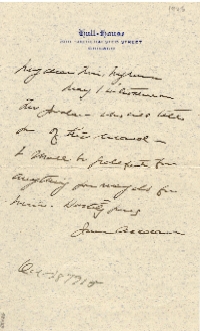

A graduate of Louisville Girls’ High School, Louisville Normal School, and the University of Louisville, Frances Ingram became the Head Resident of Neighborhood House, a Louisville settlement home, in 1905. Additionally, Ingram sat on the boards of the Louisville-Jefferson County Children’s Home and the Louisville Industrial School of Reform and was a member of numerous national, state, and local social work organizations. As a result, she corresponded with such notable reformers as Jane Addams, John Dewey, and Mary Anderson, the Director of the Department of Labor’s Women’s Bureau.

From 1905 to 1939, Ingram served

as Head Resident of Louisville’s Neighborhood

House social settlement, now

located in Portland. Originally operating

in a neighborhood on First Street,

the settlement house served several

functions. It worked with “local, state

and national agencies for reform and

protective measures,” managed playgrounds

and other facilities, and served

“as a non-sectarian meeting place for

[the] neighborhood.” The Ingram

Papers at The Filson contain a number

of documents related to the everyday

activities of Neighborhood

House. The nature of the

community surrounding

Neighborhood

House and Ingram’s

intimate contact

with its residents

encouraged her

to focus on two

major issues

during her career:

Americanization

and child welfare.

In addition

to the day-to-day

administration of

Neighborhood House,

Ingram also worked to

acclimate immigrants to Louisville

society. Working mainly with Syrian,

Italian, and German immigrants,

Ingram and Neighborhood House held

citizenship classes to teach prospective

citizens the history of the United States

and the tenets of democracy. Although

other citizenship classes existed in the

early-1900s, Neighborhood House’s

class was the only one like it operating

in the state by the 1930s. Financed in

part and encouraged by local chapters

of the American Legion, Daughters of

the American Revolution, and other

similar organizations, the citizenship

classes enabled foreign-born residents

of Louisville to earn their first set of

papers and eventually become citizens.

The Ingram Papers contain correspondence,

speeches, and articles related

to this Americanization process in

Louisville and across the country.

From 1905 to 1939, Ingram served

as Head Resident of Louisville’s Neighborhood

House social settlement, now

located in Portland. Originally operating

in a neighborhood on First Street,

the settlement house served several

functions. It worked with “local, state

and national agencies for reform and

protective measures,” managed playgrounds

and other facilities, and served

“as a non-sectarian meeting place for

[the] neighborhood.” The Ingram

Papers at The Filson contain a number

of documents related to the everyday

activities of Neighborhood

House. The nature of the

community surrounding

Neighborhood

House and Ingram’s

intimate contact

with its residents

encouraged her

to focus on two

major issues

during her career:

Americanization

and child welfare.

In addition

to the day-to-day

administration of

Neighborhood House,

Ingram also worked to

acclimate immigrants to Louisville

society. Working mainly with Syrian,

Italian, and German immigrants,

Ingram and Neighborhood House held

citizenship classes to teach prospective

citizens the history of the United States

and the tenets of democracy. Although

other citizenship classes existed in the

early-1900s, Neighborhood House’s

class was the only one like it operating

in the state by the 1930s. Financed in

part and encouraged by local chapters

of the American Legion, Daughters of

the American Revolution, and other

similar organizations, the citizenship

classes enabled foreign-born residents

of Louisville to earn their first set of

papers and eventually become citizens.

The Ingram Papers contain correspondence,

speeches, and articles related

to this Americanization process in

Louisville and across the country.

Although Americanization was

an important part of Neighborhood

House’s programs, the issue of child

welfare was Ingram’s primary concern.

Through her social work, Ingram

witnessed the underbelly of Louisville

society, and she worked to protect

Louisville’s youths from the city’s vices.

In her continuous efforts to better conditions

for the city’s children, Ingram

worked to establish a series of parks

and playgrounds, which would provide

places for youths to spend their

recreation time rather than in dance

halls or the vice district providing

opportunities for Louisville’s youths to

be involved in more acceptable activities,

including music and drama clubs,

Neighborhood House hoped to shelter

the city’s children from the “demoralizing influences” of drinking, drug

abuse, and prostitution.

Although Americanization was

an important part of Neighborhood

House’s programs, the issue of child

welfare was Ingram’s primary concern.

Through her social work, Ingram

witnessed the underbelly of Louisville

society, and she worked to protect

Louisville’s youths from the city’s vices.

In her continuous efforts to better conditions

for the city’s children, Ingram

worked to establish a series of parks

and playgrounds, which would provide

places for youths to spend their

recreation time rather than in dance

halls or the vice district providing

opportunities for Louisville’s youths to

be involved in more acceptable activities,

including music and drama clubs,

Neighborhood House hoped to shelter

the city’s children from the “demoralizing influences” of drinking, drug

abuse, and prostitution.

In 1933, when the Jefferson County White House Conference prepared a report on “Youth Outside of Home and School,” its members visited thirty pool rooms in Louisville to investigate children’s easy access to such locations. The reporters found swearing, drinking, pool-shooting children in almost all the establishments examined. The Youth Outside of Home and School Committee, chaired by Ingram, deemed only four of the thirty pool rooms “suitable places for men and boys,” and they found three of the pool rooms so despicable as to report them to the Directors of Safety and Health. Although the report contained a summary of findings, the Ingram Papers at The Filson include the complete results of the investigation and descriptions of the halls inspected. The investigators’ reports provide detailed accounts of “prostitutes, drink, and suggestive dancing [that] were the dominating features” of the seedier pool halls.

In addition to pool rooms, Louisville’s

dance halls concerned Ingram.

During World War I, Ingram served as

Chairman of the Welfare Committee of

the War Recreation Board and attempted

to curtail “improper conduct” at

dances held in dance halls, hotels, and

other venues across the city. Ingram

was troubled by “tight holding” in

dances such as the “Turkey Trot” and

the “Arizona Anguish” as well as the

sale of liquor at dance halls. Hoping

to curtail lewd behavior at dancing

venues in the city, Ingram proposed a

series of regulations, including banning

admission of children under sixteen,

“dancing in darkness or by lowered

lights,” and “side motions of hips and

shoulders.” She also suggested providing

a member of the War Recreation

Board to demonstrate proper dancing.

Additionally, the Board founded its

own dance hall, Ha-wi-an Gardens, to

provide “wholesome recreation” for

soldiers at Camp Zachary Taylor and

the community at large. Ingram’s

attempt to sanitize Louisville’s dance

halls is documented in the collection

through a variety of correspondence,

reports, and investigations.

While not as wide spread as billiards

and “ugly dancing,” the social

ills of alcohol, drugs, and prostitution

also troubled Ingram. Although these“ abominations which menace youth”

were mostly confined to the red-light

district on Green Street (now Liberty),

child laborers – particularly night-shift

messenger boys – were likely to witness

and experience the carnal offerings of

the city’s vice district. Night messengers

were often sent to deliver

messages to Green Street’s brothels

when working the 6 P.M. to 2 A.M.

shift. The late-shift messenger boys of

Louisville and other cities came to the

attention of the National Child Labor

Committee, which sent investigators to

Louisville in the late-1900s and 1910s

to examine the problem. Included in

the Ingram collection are several of

the NCLC’s investigative reports on

Louisville’s messengers. These graphic

reports describe the conditions in the

vice district and the numerous ways

that messengers were able to earn large

tips and extra income for providing

alcohol, drugs, sex, and other “favors”

to prostitutes and other denizens of the

red-light district.

In addition to pool rooms, Louisville’s

dance halls concerned Ingram.

During World War I, Ingram served as

Chairman of the Welfare Committee of

the War Recreation Board and attempted

to curtail “improper conduct” at

dances held in dance halls, hotels, and

other venues across the city. Ingram

was troubled by “tight holding” in

dances such as the “Turkey Trot” and

the “Arizona Anguish” as well as the

sale of liquor at dance halls. Hoping

to curtail lewd behavior at dancing

venues in the city, Ingram proposed a

series of regulations, including banning

admission of children under sixteen,

“dancing in darkness or by lowered

lights,” and “side motions of hips and

shoulders.” She also suggested providing

a member of the War Recreation

Board to demonstrate proper dancing.

Additionally, the Board founded its

own dance hall, Ha-wi-an Gardens, to

provide “wholesome recreation” for

soldiers at Camp Zachary Taylor and

the community at large. Ingram’s

attempt to sanitize Louisville’s dance

halls is documented in the collection

through a variety of correspondence,

reports, and investigations.

While not as wide spread as billiards

and “ugly dancing,” the social

ills of alcohol, drugs, and prostitution

also troubled Ingram. Although these“ abominations which menace youth”

were mostly confined to the red-light

district on Green Street (now Liberty),

child laborers – particularly night-shift

messenger boys – were likely to witness

and experience the carnal offerings of

the city’s vice district. Night messengers

were often sent to deliver

messages to Green Street’s brothels

when working the 6 P.M. to 2 A.M.

shift. The late-shift messenger boys of

Louisville and other cities came to the

attention of the National Child Labor

Committee, which sent investigators to

Louisville in the late-1900s and 1910s

to examine the problem. Included in

the Ingram collection are several of

the NCLC’s investigative reports on

Louisville’s messengers. These graphic

reports describe the conditions in the

vice district and the numerous ways

that messengers were able to earn large

tips and extra income for providing

alcohol, drugs, sex, and other “favors”

to prostitutes and other denizens of the

red-light district.

Because of these “unwholesome

influences,” Ingram and others worked

to establish supervised recreation

areas in Louisville. Most important

for this movement was the building of

playgrounds. By building supervised

playgrounds, Louisville’s activists

hoped to help children build “character

. . . through the

formation of ideals

and standards and

social adjustments

. . . which prepare

the individual for

later life.” Ingram

and her allies

intended to provide

a wholesome

atmosphere for

Louisville’s youth

and protect them

through supervision of their leisure activities.

Ingram’s correspondence and

the reports and articles she gathered

illustrate the goals of the recreation

movement in Louisville.

Because of these “unwholesome

influences,” Ingram and others worked

to establish supervised recreation

areas in Louisville. Most important

for this movement was the building of

playgrounds. By building supervised

playgrounds, Louisville’s activists

hoped to help children build “character

. . . through the

formation of ideals

and standards and

social adjustments

. . . which prepare

the individual for

later life.” Ingram

and her allies

intended to provide

a wholesome

atmosphere for

Louisville’s youth

and protect them

through supervision of their leisure activities.

Ingram’s correspondence and

the reports and articles she gathered

illustrate the goals of the recreation

movement in Louisville.

Often, the best way to avoid the lures of urban immorality was to leave the city. In Pewee Valley in the 1910s, Louisvillians established the Louisville Fresh Air Home, which served as a summer camp for Neighborhood House. Described as a “veritable haven of rest to the city’s tired mothers and a source of joy to their children,” the Fresh Air Home offered multiple weeklong programs during the summer that allowed mothers and children to escape the city. Each summer during the 1920s and 1930s, the Fresh Air Home hosted anywhere from five hundred to a thousand campers, who enjoyed opportunities for swimming, hiking, and other activities offered by the camp’s rural location.

While Ingram and Neighborhood

House worked to assist immigrants

and to protect children, their mission

also included helping the community

at large. During the Great Depression, The settlement’s actions during the

1937 flood also demonstrated Neighborhood

House’s community outreach.

While much of the city lay under

water, Neighborhood House’s canteen

remained open and served meals to

flood refugees. Extensive correspondence

from early 1937 suggests that

Neighborhood House became a center

for the flood relief effort, receiving

donations from across the country.

While Ingram and Neighborhood

House worked to assist immigrants

and to protect children, their mission

also included helping the community

at large. During the Great Depression, The settlement’s actions during the

1937 flood also demonstrated Neighborhood

House’s community outreach.

While much of the city lay under

water, Neighborhood House’s canteen

remained open and served meals to

flood refugees. Extensive correspondence

from early 1937 suggests that

Neighborhood House became a center

for the flood relief effort, receiving

donations from across the country.

The Francis MacGregor Ingram collection provides an in-depth look at social reform movements in early-twentieth century Louisville and the United States. Because of Ingram’s local and national role in social organizations, her papers record the trajectory of many important reform campaigns from the 1900s to the 1950s. With correspondence from other social workers and social organizations, as well as reports, lectures, essays, and other materials, Ingram’s papers give researchers a window into the early social reform movements in Louisville as well as providing information on similar efforts across the United States.

The Filson Historical Society

1310 South Third Street - Louisville, KY 40208

Phone: (502) 635-5083 Fax: (502) 635-5086

Hours

The Ferguson Mansion and Office

Monday - Friday: 9 am. - 5 pm.

Saturday and Sunday closed

Library

Monday - Friday: 9 am. - 5 pm.

Saturday: 9 am. - 12 noon