19th Century Distilling Papers at The Filson

By Michael R. Veach

Special Collections Assistant

About |

Many historians state that the 19th century starts with the French Revolution and ends with

the Great War. It can also be said that the 19th century distilling industry starts with the whiskey

rebellion and ends with prohibition, covering roughly the same time period.

Many historians state that the 19th century starts with the French Revolution and ends with

the Great War. It can also be said that the 19th century distilling industry starts with the whiskey

rebellion and ends with prohibition, covering roughly the same time period.

Since we looked at “Early Distilling Papers at The Filson” in a previous issue (Vol.5, No.3, Summer 2005), we will start here in the 1830s.

The distilling industry in the 1830s was beginning to shift from the farm to the city through “rectifiers” – merchants who bought whiskey from farmer distillers and “rectified” it to sell as their own brand. This process could be anything from simply aging the product to adding sugar and other flavoring agents to the alcohol to make a product more appealing to consumers. Most whiskey was sold by the barrel but many companies started bottling their product to sell to the consumer in the 1830s. The Filson has a scrapbook of labels produced by printer Henry Miller in the 1840s and 50s that include many labels for bourbon and rye.

The distillers in the first half

of the 19th century used pot still

technology and The Filson has a

Henry Clay legal brief that gives

a description of a typical pot still.

Clay is representing his cousin

Green Clay in a case against

George Coons and John Cock

for failure to deliver his still. The

invention of the column still in

1830 by Aeneas Coffey in Ireland created a method

of distilling large amounts

of whiskey for a small

amount of money. This

allowed larger distilleries to

locate in cities and towns

with their supply of grain

coming to them by railroad.

It also allowed them

to produce higher proof

spirits that could be blended with

whiskey by rectifiers to create

cheap products.

Ireland created a method

of distilling large amounts

of whiskey for a small

amount of money. This

allowed larger distilleries to

locate in cities and towns

with their supply of grain

coming to them by railroad.

It also allowed them

to produce higher proof

spirits that could be blended with

whiskey by rectifiers to create

cheap products.

In the 1830’s James Crow became the distiller for Oscar Pepper at his Woodford County distillery. Crow started using scientific methods to measure such things as pH and temperature during the distillation process to document the process and its changes. The measurements made it easier to duplicate the process and make a consistent product. It was Crow’s quality of whiskey that E. H. Taylor, Jr. wished to produce when he entered the business after the Civil War. The Filson is fortunate to have records pertaining to E.H. Taylor, Jr. in the Taylor-Hay Family Papers.

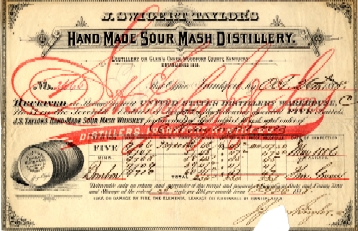

Before entering the distilling business, Taylor took a tour of distilleries in Scotland, Ireland, Germany, and France to see for himself the most modern processes and distillery layouts. Upon his return to Kentucky his first project was helping with the design of the “Hermitage Distillery” for Gaines, Berry and Co. who owned the Old Crow brand at the time. A few years later he purchased an old distillery on the Kentucky River and rebuilt it as the “OFC Distillery” which started production in 1870. The Taylor-Hay Family Papers include Taylor’s correspondence from this period along with business receipts, letterpress books and distilling ledgers.

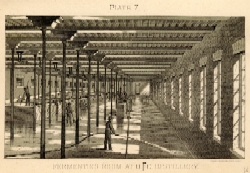

The “OFC Distillery” was an

“Old Fashioned Copper” distillery

that used pot stills and

small mash tubs to make a true

sour mash whiskey. Taylor was a

straight whiskey distiller and saw

the rectifiers as his main competition.

Taylor and others believed

that the rectifiers, who produced

an imitation bourbon using

neutral spirits and flavoring in

less than a day, were damaging

the tradition of quality aged

Kentucky whiskey. He was not

the only distiller who took this attitude.

Other distillers who agreed

with Taylor testified before Congress

and argued for the increase

of the Bonding Period for whiskey.

The Filson has his testimony

as recorded in the Congressional

Record for 27 July 1888 in the

library pamphlet collection. In

this pamphlet, distiller John

Atherton states that it is understood

in the industry that

Kentucky Whiskey is made for

the purpose of aging and most

often sold straight. He also goes

into detail on how the whiskey

is made and aged.

The “OFC Distillery” was an

“Old Fashioned Copper” distillery

that used pot stills and

small mash tubs to make a true

sour mash whiskey. Taylor was a

straight whiskey distiller and saw

the rectifiers as his main competition.

Taylor and others believed

that the rectifiers, who produced

an imitation bourbon using

neutral spirits and flavoring in

less than a day, were damaging

the tradition of quality aged

Kentucky whiskey. He was not

the only distiller who took this attitude.

Other distillers who agreed

with Taylor testified before Congress

and argued for the increase

of the Bonding Period for whiskey.

The Filson has his testimony

as recorded in the Congressional

Record for 27 July 1888 in the

library pamphlet collection. In

this pamphlet, distiller John

Atherton states that it is understood

in the industry that

Kentucky Whiskey is made for

the purpose of aging and most

often sold straight. He also goes

into detail on how the whiskey

is made and aged.

In the late 19th century most whiskey was sold by the barrel to a liquor store, druggist or tavern. The whiskey was then sold to consumers who would often bring in their own bottle or jug, but distilleries and rectifiers often offered jugs for sale to the consumer. The Filson has the J. D. Barnett Collection of stoneware jugs that are fine examples of typical 19th century whiskey jugs. Taverns would serve the whiskey to their customers by filling a bar decanter from the barrel when needed. Individuals could also purchase a full barrel and decant the whiskey as needed. The Filson Museum also has several nice examples of 19th century decanters.

After the Civil War there were

many changes in the distilling

industry. In 1879 Fredrick Stitzel

patented the system of barrel

racks that is still used in bourbon

warehouses to store barrels today.

The Filson has his patent model

in its museum collection. In 1870,

George Garvin Brown

created the Old Forrester

brand of whiskey

and decided to sell it only

by the bottle in order to

guarantee the consistent

quality of the whiskey for

the medical trade. Brand

names became a very

important part of the industry

and advertising for

these brands began to appear.

The Filson has some

of this advertising art in its

museum collection including

an “I. W. Harper”

hunting scene on glass, an

“Old Dixie” oil painting

and a W. L. Weller “Mammoth

Cave” silk banner.

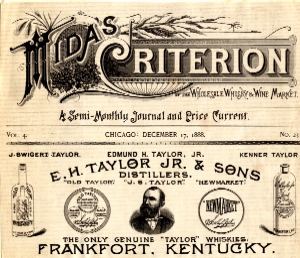

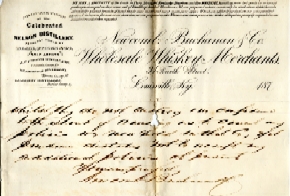

Letterheads are another source of

advertisement and The Filson has

several collections with examples

of distilling letterhead. The papers

for the 1895 Grand Army of the

Republic Encampment and the

Taylor-Hay Family Papers are

both rich with examples of

distillery letterhead.

After the Civil War there were

many changes in the distilling

industry. In 1879 Fredrick Stitzel

patented the system of barrel

racks that is still used in bourbon

warehouses to store barrels today.

The Filson has his patent model

in its museum collection. In 1870,

George Garvin Brown

created the Old Forrester

brand of whiskey

and decided to sell it only

by the bottle in order to

guarantee the consistent

quality of the whiskey for

the medical trade. Brand

names became a very

important part of the industry

and advertising for

these brands began to appear.

The Filson has some

of this advertising art in its

museum collection including

an “I. W. Harper”

hunting scene on glass, an

“Old Dixie” oil painting

and a W. L. Weller “Mammoth

Cave” silk banner.

Letterheads are another source of

advertisement and The Filson has

several collections with examples

of distilling letterhead. The papers

for the 1895 Grand Army of the

Republic Encampment and the

Taylor-Hay Family Papers are

both rich with examples of

distillery letterhead.

The library at The Filson is a

very good source for information

on 19th century distilling. Louisville

City Directories have ad-

dresses and often advertisements

for distillers and rectifiers. In the

Rare Books  collection, there are

also several Louisville Business

Directories that give the location

of Louisville businesses including

distilleries and a brief description

and history of firms. These volumes

are indexed by firm names

and personal names. This index

was compiled by retired Filson

Librarian Dorothy Rush. Also

in the Rare Books collection is

a copy of the book A History of

Kentucky Distilling Interest published

by the Kentucky Distillers Bureau

of Lexington in 1893 that has

descriptions and brief histories

of distilling firms throughout

the state.

collection, there are

also several Louisville Business

Directories that give the location

of Louisville businesses including

distilleries and a brief description

and history of firms. These volumes

are indexed by firm names

and personal names. This index

was compiled by retired Filson

Librarian Dorothy Rush. Also

in the Rare Books collection is

a copy of the book A History of

Kentucky Distilling Interest published

by the Kentucky Distillers Bureau

of Lexington in 1893 that has

descriptions and brief histories

of distilling firms throughout

the state.

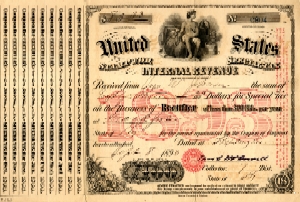

The end of the 19th century saw the passage of the Bottled-In- Bond Act of 1897. E.H. Taylor, Jr. played a significant role in getting this law passed and then promoting Bonded Whiskey in the U.S. market. “Bottled-In-Bond” whiskey must be all from the same distillery, made in the same season, aged at least four years, and bottled at 100 proof. At the time this law was seen as a model for future Pure Food and Drug laws. The Taylor-Hay Family Papers have three scrapbooks put together by E H Taylor, Jr. with many articles dealing with his efforts to promote Bonded Whiskey in the early 20th century.

The distilling industry played an

important role in the 19th century

Kentucky economy. Kentucky had

hundreds of distilleries and rectifying

companies who provided

jobs and paid taxes, thereby helping

to support the government before

there was an income tax. The

20th century saw a huge change in

the business leading to the companies

and brands we know today.

The Filson has many sources

including both published materials

and original manuscripts, as well

as artifacts that are of interest to

anyone researching 19th century

distilling in Kentucky.

The distilling industry played an

important role in the 19th century

Kentucky economy. Kentucky had

hundreds of distilleries and rectifying

companies who provided

jobs and paid taxes, thereby helping

to support the government before

there was an income tax. The

20th century saw a huge change in

the business leading to the companies

and brands we know today.

The Filson has many sources

including both published materials

and original manuscripts, as well

as artifacts that are of interest to

anyone researching 19th century

distilling in Kentucky.

The Filson Historical Society

1310 South Third Street - Louisville, KY 40208

Phone: (502) 635-5083 Fax: (502) 635-5086

Hours

The Ferguson Mansion and Office

Monday - Friday: 9 am. - 5 pm.

Saturday and Sunday closed

Library

Monday - Friday: 9 am. - 5 pm.

Saturday: 9 am. - 12 noon